Table of content

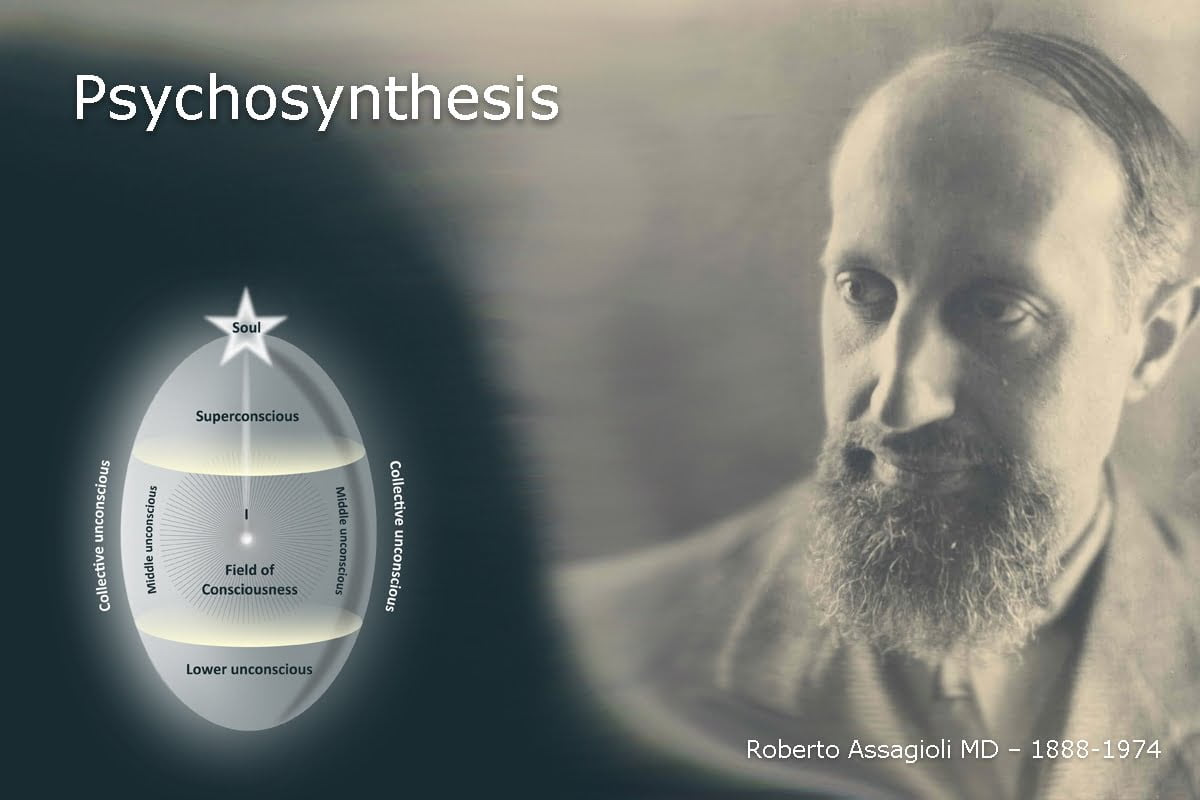

Stuart Miller, a Director of Esalen Institute,[i] describes the impact and effect on him of Psychosynthesis and Roberto Assagioli, its inventor.

By Stuart Miller, Re-formatted and Edited With Notes by Jan Kuniholm in 2024

Abstract: In the article below on his personal experience, Stuart Miller, a Director of Esalen Institute,[i] describes the impact and effect on him of Psychosynthesis and Roberto Assagioli, its inventor. Miller is one of the people chiefly responsible for guiding Esalen in new directions and seeking out those disciplines of personal growth which seem most effective. Both he and Michael Murphy, Esalen’s founder, having worked with literally hundreds of systems for personal development, feel that psychosynthesis presents certain advantages that will make it useful on an ever wider scale for the millions of Americans who are turning to the task of developing themselves as people. They don’t claim that it’s the answer, but they do say it provides a framework for getting more and larger answers. As Murphy recently wrote: “After years of exploration with countless approaches to personal growth and education, we have felt an increasing need for a unifying understanding of human nature and a comprehensive discipline. Psychosynthesis promises to fill that need.” Their idea is not that psychosynthesis will replace other techniques but, rather, that it will provide a framework for using them.

We asked Stuart Miller to introduce his personal account by giving our reader some more objective answers about psychosynthesis in an interview with Popular Psychology. — Editors, Popular Psychology[ii]

Stuart Miller: My Personal Experience with Psychosynthesis[iii]

Michael Murphy, the President of Esalen Institute, my wife and I were in England in the summer of 1970 looking into new developments that might be of interest to Esalen. In many ways it had been a disappointing visit. The English had greeted many of the things we brought to them with great excitement — encounter, sensory awareness, forms of meditation, the theory of developing the human potential. But I had hoped to find something new for Esalen and myself. How annoying, after all the work I had done on myself with the help of Esalen, to be still so dissatisfied. And then, of course, I wondered a lot in the muggy June weather of London if the enthusiasm with which the English were greeting us would last. What we had brought them was exciting and important but there was also something missing in what Esalen had to offer.

We got a letter from Jim Vargiu[iv] inviting us to do a week of didactic psychosynthesis with Roberto Assagioli. I didn’t know anything about psychosynthesis, but I knew Assagioli’s name as one of the founders of the Association of Humanistic Psychology. I thought it was proper, since we were in Europe, that we meet him. The three of us flew down to Florence, and shortly after our arrival we met with Assagioli for a brief welcome. He impressed me: a tall man, slightly bent over at the shoulders with age, his eyes seemingly endless like Fritz Perls’ eyes had been, endowed with the same statement of spiritual authority, but cheerful. He was very cheerful. So many of the teachers I had met, including Fritz himself, had not had this air of light gaiety.

I was intrigued by the, to me, paradoxical combination of deep authority and lightness. We began visiting him once or twice a day and he would give us little seminars. We would write our questions on a pad and show them to him, because he was deaf. He was incredibly alert and would pounce down his answers with a twinkle in his eyes,

Some of the things he said disturbed me very much. He said that the basic method of psychosynthesis was to develop a person’s ability to act from his best center. This sounded, to me, so opposite to the teachings of encounter and gestalt that I accused him of being unfaithful to the human experience. I told him that he was recommending ‘‘phoniness.” Then he explained to me that there might not be any contradiction between psychosynthesis and such methods as encounter and gestalt, but that, to begin with, it is important to get straight what was “phony” and what was “real.” To be real, he ‘explained, is not the same as being true to one’s neurosis, or hangups, or one’s negativity. These, he said, cannot be ignored or repressed. But they are not real in the same sense that our true “Self” is real — the part of us which is the seat of our consciousness and our highest aspiration and knowledge.

Of course, you will say. But I had forgotten. Lost in some of the methods of self-improvement, I had forgotten the purpose of many of the techniques associated with Esalen. The purpose was, presumably, to develop myself into a better human being. It was for this reason that I would learn to contact my anger in an encounter group or investigate my demons in Gestalt therapy. But I had forgotten the purpose and gotten lost in mere technique. The first important thing that psychosynthesis did for me was to liberate me from the thralldom of my negative emotions and thoughts. It recalled to me what I always knew, namely, that at the heart of my being, as well as everyone else’s, there was divinity, however latent to a degree. Since these first meetings, Assagioli and psychosynthesis have helped me to remember who, essentially, I really am, though I must confess that I still forget more frequently than I would like.

What with all this emphasis on the positive aspects of my self, the marvelous thing, from the very beginning, was that psychosynthesis didn’t seem to ask for really important sacrifices. I did not have to give up the explorations that techniques like encounter, gestalt and bio-energetics had led me to. Instead, I could use these but this time without losing sight of my higher self and my pervasive aim which is to develop my personality in tune with what is highest in me. As the days went on in Florence I began to see, in talking with Assagioli and reading his work, that psychosynthesis showed me a framework in which I could find liberation from the personal nonsense which torments me, without denying the existence and the peculiar reality of that nonsense. I began to feel that I had a new direction without having to exclude what I had already learned.

Furthermore, psychosynthesis had a generous quality; just as it did not exclude aspects of the psyche, so it didn’t exclude other techniques and approaches. I had heard so many irritated teachers denounce the work of other teachers. And that had been hard, because I had seen value in all of them. Assagioli excluded no plausible technique, but he did seem to know of a place from which one could judge when and where and for whom a technique might be valuable. His openness toward the myriad of Esalen approaches seemed predicated on some steady vision of the nature of human development. I began to think that his approach could provide a framework for the synthesis of Esalen techniques.

So you can see that it didn’t take me very long to be impressed with his wisdom and tremendous insight. It didn’t take me long to be impressed by the magic of his presence. But there was more than that. Here for once was a guru who wore a tie, who had an office, a gentle sense of humor, who lived in a city. There was no white robe, or silver chalice, drums, gongs, beads, and incense in his house. I have nothing against such items, but they are really not my personal trip. I want as much enlightenment as I can get and I want to live in a city, have a job, be socially useful, have a family, wear conventional clothes, and all the rest of it. His presence then and ever since has always assured me that it is possible to develop one’s self in very, very high ways and still to stay in the world and be in other ways rather conventional.

As time went on and I read more of what he had written and studied with him, I came to see that this allowing of the normal was part of the spirit of psychosynthesis. There was an implication that, for some people it was normal to do rather strange things in their spiritual pursuit, and that for many others it was normal to be rather normal in many ways, and also that it was normal for them to have spiritual pursuits, too. The quest was normal for all and the means need not be far-out. The means could be gradual. Ten minutes a day of meditation was not the same as committing oneself to a monastery, but it might still be a very good thing in helping oneself and the world along in just a small way. Pursuing the synthesis of one’s own psychic functions a few minutes a day and then as an increasingly pervasive attitude in one’s life is, after all, a little step forward, and, in fact, such little steps may be enough for most of us. I felt a permission from Assagioli and his writings to stay myself, remain Stuart Miller, and still go on.

I have since come to understand and agree with some of the deeper insights of psychosynthesis, finally seeing it not even as a master discipline but rather as a natural process, pervasive in all men, which Assagioli has only named and given us a strategy for assisting. It is a process that is integral, unifying the personality in more and more harmonious ways, and lifting that integration to higher and higher levels. One can, if he looks, see it happening everywhere, not unaccompanied by obstacles, backslides, and enormous resistances. The achievement of Psychosynthesis, with a capital “P,” is to suggest the outlines of a comprehensive method for assisting this natural process by using all that we know about human development. It is not a work which Assagioli has exhausted. In fact he likes to say that Psychosynthesis (again with a capital “P”) is only just beginning. I tend to think he is right.

Laura Huxley, Aldous Huxley’s widow, told me long after my first visit to Dr. Assagioli that she thought much of what he had to say was “good Latin common sense.” She has a point. And perhaps common sense derived from the collective wisdom of the Mediterranean people is one thing many of us can use as we plunge into the heady stuff of the human potential movement. Then there was a lot that was ordinary about Assagioli and that was a great comfort to me. Perhaps I can say one last thing which may be of help, and that is that the depth and subtlety of Assagioli’s work and that of his students is often not immediately apparent because they write with deceptive simplicity. I have learned that it takes very careful reading and slow reading to catch the magic. ■

Interview[v] With Roberto Assagioli[vi]

Stuart Miller: What is Psychosynthesis?

Roberto Assagioli: It is not a technique. That’s clear. Nor is it a specific psychological theory or a philosophy. Pragmatic in spirit, psychosynthesis includes techniques, makes some important theoretical statements, and remains carefully less than systematic. It is an open-ended approach to taking into account all the known facts about man’s inner life. In a sense, as I make clear in my personal statement, psychosynthesis with a small “p” is a natural process, something that is going on all the time, and Psychosynthesis with a capital “P” is just the sum of all the information we have about how to enhance and accelerate that process.

Stuart Miller: What process are you talking about?

Roberto Assagioli: I mean the process of the harmonization of personality. Two of the key concepts of psychosynthesis are the Self and the personal functions. The idea of harmonizing the personality is an old one, but put here into modern psychological language.

Stuart Miller: Much of Assagioli’s contribution is just that, updating our understanding of old and sometimes lost notions. By the Self, Assagioli means, first of all, the core of the personality; what Freud, himself, called the ego; what comes to mind when we say “I.” For Assagioli, it is, above everything, the experience of self-awareness.

Roberto Assagioli: We go to sleep at night and this experience disappears. We awake, and we’ve suddenly got it back. Now, part of the problems we all have is accounted for by the fact that we forget our Selves, too often, while we are awake. We identify with the contents of our consciousness or with roles.

Stuart Miller: Why is that so bad?

Roberto Assagioli: It isn’t bad, necessarily, but it can and frequently does get us into trouble. To take a simple example, instead of identifying himself with himself, a businessman can identify himself with the role of being a businessman. So he comes to feel that his very Self depends on his being successful, his very identity. That is, of course, an illusion. His Self is his, he exists, the fault is in not remembering. But you see businessmen who forget so much that they drive themselves to ulcers and even to suicide. Remember the bankrupt millionaires who dived out of windows during the Crash of ’29. They forgot who they were. Trouble is that so many of us are so attached to identifying with parts of our personalities that we forget our Selves: we become the student, the mother, the child, the gambler, the lover. That’s all right for us when things are going well, but it’s terrible when things go badly.

Stuart Miller: It sounds like you are talking about a fundamental issue of human freedom.

Roberto Assagioli: Yes. The Self is the locus of human freedom. Remember your Self, stay conscious of the experience of self- awareness and you are free to meet life.

Stuart Miller: To Assagioli, this is basic, and it frequently brings him to use the image of the orchestra conductor.

Roberto Assagioli: If one can operate from his self-conscious center, remembering who he is, then he can use the various elements of his personality. Instead of letting them use him. So one can choose to be the teacher or the lover or the businessman at will, and turn those roles off, at will.

Stuart Miller: How does one learn how to do that? It sounds easy to say but hard to achieve.

Stuart Miller: It is hard, and one shouldn’t be deceived in reading Assagioli into thinking that what he talks about can be easily achieved. He himself says that just because he tries to write about these things simply doesn’t mean that they are simple to achieve.

Roberto Assagioli: On the other hand, they aren’t that complicated or hard. I mean that we have found that a little bit of regular effort, even a few minutes a day, can pay enormous dividends. One place to start is simply by learning first to recognize and then to disidentify from everything but the Self: emotions, the body, your thoughts, all the roles. A lot of people think, for example, that they are their thoughts, but a moment of introspection will show them that there is somebody behind their thoughts. I mean that each of us can observe his thoughts. So, who is the observer? The Self, of course.

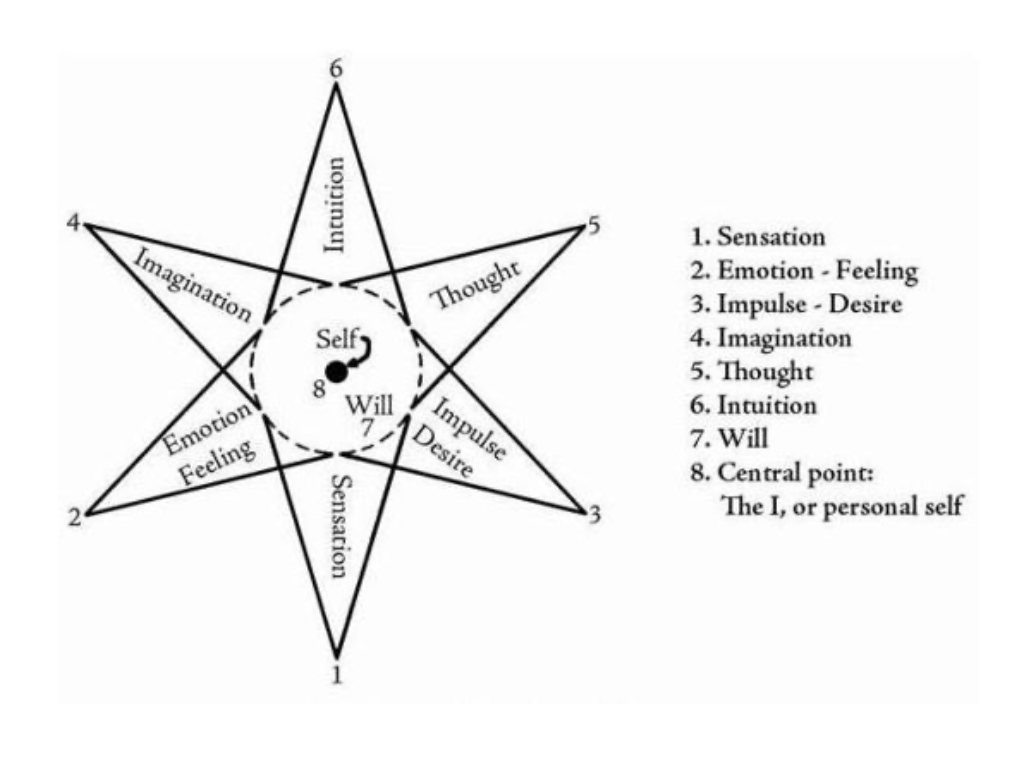

Stuart Miller: Learning to self-identify can provide the base for becoming the conductor of the orchestra of the personality. One diagram that Assagioli uses may help here.

The self, at the center, can gradually disentangle itself from the other personality functions and learn to control and harmonize them.

In this way, for instance, instead of being a victim of one’s emotions, one can learn to dominate them. Thus, one can be angry at will, or even happy, at will.

Stuart Miller: I’m amazed to hear all this talk about controlling emotions, and even about control in general. After all, if Esalen has become famous for any one thing it is the wisdom of giving up control, of letting go.

Roberto Assagioli: This is a subtle matter and pretty complicated, but I’ll try to give you a brief answer. One problem which many people have in our society, and one reason why many come to Esalen, is that they are too controlled. So many of them say that they can’t feel and they want to learn how. Others say that their bodies are too tight and they want to let go. Still others say they think too much and they want to get out of their heads.

They are right, of course; they are controlled. But it is not they, not their Selves, which is doing the controlling, Instead, it is their identification with one or another psychological role or function. The over-intellectualized engineer who comes to Esalen saying he wants to “get out of his head,” is controlled by certain aspects of his mind and by his sub-personality that identifies him with functional thinking. In the star diagram, he would be all mind and the other functions would be tiny shadows; the Self would be outside the diagram altogether. So, the first thing he must learn is that he has feelings, that he has imagination, and so on. That he is more complete than he thinks. To learn that he must allow the thinking sub-personality controlling him to let go of him. In the process, a curious thing happens: people become conscious not only of unused psychological functions, they also become conscious of personal power, of themselves. So, the first stage is release from outer control, then self-identification, then development in a harmonious way of all the powers we have.

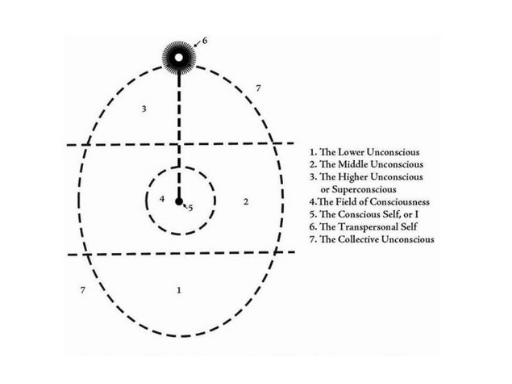

Stuart Miller: This is all so conscious, so premeditated. Doesn’t Assagioli recognize the unconscious and all its demons? Certainly. In fact, Assagioli was one of the pioneers of psychoanalysis in Italy, in 1910. He knew Freud, personally, and was a co-worker of Jung. And he believes that the unconscious is one of the great discoveries of modern psychology. However, he has a wonderfully broad-gauge understanding of the unconscious. Freud and most of his followers in psychoanalysis emphasized the lower aspects of the unconscious: animal drives and so forth. Assagioli believes that there are, roughly speaking, three levels of the unconscious.He uses another diagram to illustrate this.

Roberto Assagioli: The lower unconscious, Number 1, is what Freud mostly talked about. It is the primitive man, both individually and as a species. The middle unconscious is all that we are unconscious of in everyday life—for example, the thoughts and images flashing through our minds and imaginations, errands we can remember to do or may forget, and so on. The higher unconscious, however, is relatively unexplored by modern psychology and it is also a strong ally, if mobilized, in the process of making ourselves into all we want to be. The superconscious, or higher unconscious, is the source of artistic inspiration, of ethical inspiration, of religious experience, of moral inspiration. And it can seem to be even outside of us. So poets traditionally refer to the Muse as the source of their inspiration.

One of the things that a lot of people have been waking up to in our culture is that the superconscious can be cultivated, that ways can be found to bring its contents down, out into the open. A lot of the enthusiasm for various meditative techniques, inner imagery work, and creativity training comes from this realization. By evoking these higher energies — some call them “trans-personal” — one gains a strong ally in the process of synthesizing one’s personality.

Stuart Miller: It still sounds a little facile. What about the Freudian demons, the dark forces within us? Are they ignored?

Roberto Assagioli: Not at all. In practice, Psychosynthesis, when practiced by an educator or a therapist, begins with an “analytic” phase. In the sense of “psychoanalytic.” By that is meant that one attempts to analyze the blockages to personal development and then to analyze their causes. One might even use the techniques of classical analysis: free association and so forth. However, one is not limited to Freudian techniques in dealing with blockages. Many active techniques can be used to give perspective on and freedom from a childhood problem with a parent, for example. So, one can use not only free association, talk, and dream analysis, but also psychodrama, cathartic techniques, free drawing, and also more positive techniques like the “ideal model.” That is, imagining and acting as if one has already solved the problem.

Stuart Miller: Naturally, one must reckon with Freud: repression of problems is not solving them. On the other hand, and this is my second point, one doesn’t have to wallow endlessly in childhood remembrances, ten years on the couch, in search of cleaning out all the garbage purportedly in one’s past. That’s too frequently the approach of psychoanalysis, and I think, personally, it’s an illusion and wasteful of time. Assagioli, of course, wouldn’t use such harsh words; he’s very sunny and good-tempered. But I think that one of the advantages of psychosynthesis is that it uses psychoanalysis but doesn’t get lost in it. For me, as a director of Esalen, one of the most exciting things about Assagioli’s theories is that they provide room for all of our approaches to human growth: encounter, psychoanalysis, meditation, sensory awareness, gestalt therapy, the myriad body disciplines, transactional analysis, rational-emotive therapy, and so forth. Each and all of these can be useful to particular people at particular points in their own personal development. Thus, a man may need at various times to analyze various blocks, or learn to feel his emotional energy in encounter, or learn to use his imagination by means of inner imagery techniques.

Stuart Miller: What about this concept of “The Higher Self in the second diagram?

Roberto Assagioli: I’m glad you asked that at the end, because it allows me to say that there is an enormous amount of fundamental material we haven’t covered in this brief interview.

Stuart Miller: People who are interested can read at greater length in Assagioli’s books. The Higher Self or the Transpersonal Self is one of the subtler concepts, but I’ll put it this way. I think each of us knows that in him, related somehow to his purest identity, is an energy, perhaps one could say a being, a force, that represents the highest in him. In the old religious language, people used to call this the spirit or essence or soul. To some extent it is a mystery. But one of the most exciting things about Assagioli’s works is that he has brought this mystery into the center-of modern psychological thought, and without ever leaving behind all the more mundane realities with which each of us has to cope. ■

References to Assagioli’s books and several psychosynthesis centers which are no longer in operations were appended to the interview. —Ed.

[i] Esalen Institute is a non-profit retreat center and intentional community located in Big Sur, California, founded in 1962 by Michael Murphy and Dick Price.

[ii] Popular Psychology was published in the United States, but the history of the publication is unknown. —Ed.

[iii] We have included Stuart Miller’s personal account as being relevant to the interview which follows. —Ed.

[iv] James Vargiu was founder and director of Psychosynthesis Institute, of Palo Alto and then San Francisco, CA. Vargiu had studied psychosynthesis with Assagioli. —Ed.

[v] The Assagioli Archives lists the date of this interview, which is Doc. #24343, as 1972. Internal evidence supports this, because the end note of the published interview lists Assagioli’s book The Act of Will, as “an Esalen book, The Viking Press, to be published in Spring, 1973.” —Ed.

[vi] In the original publication of this interview, Stuart Miller’s questions to Assagioli and his own reflections based upon earlier conversations are often mixed in the layout and typeface of the interview. We have attempted to distinguish Miller’s “live” questions by setting them entirely in italics, and attempted to distinguish Assagioli’s actual responses from Miller’s reflections and commentary. —Ed.

[i] Esalen Institute is a non-profit retreat center and intentional community located in Big Sur, California, founded in 1962 by Michael Murphy and Dick Price.

Leave a Reply